Does Root Canal Treatment Work?

I often hear patients say, “My neighbor says to not get a root canal, because he’s had three of them and each of those teeth have been pulled. Do root canals work?” Although root canal failure is a reality, it happens more often than it should. When a root canal failure is present, root canal retreatment can often solve the problem. This article discusses five reasons why root canals fail, and how seeking initial root canal treatment from an endodontist can reduce the risk of root canal failure.

The ultimate reason why root canals fail is bacteria. If our mouths were sterile there would be no decay or infection, and damaged teeth could, in ways, repair themselves. So although we can attribute nearly all root canal failure to the presence of bacteria, I will discuss five common reasons why root canals fail, and why at least four of them are mostly preventable.

Although initial root canal treatment should have a success rate between 85% and 97%, depending on the circumstance, about 30% of my work as an endodontist consists of re-doing a failing root canal that was done by someone else. Root canals often fail for the following five reasons:

- Missed canals.

- Incompletely treated canals – short treatment due to ledges, complex anatomy, lack of experience, or lack of attention to quality.

- Remaining tissue.

- Fracture

- Bacterial post-treatment leakage.

1. Missed Canals

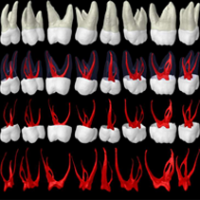

The most common reason I see for root canal failure is untreated anatomy in the form of missed canals. Our general understanding of tooth anatomy should lead the practitioner to be able to find all the canals. For example, some teeth will have two canals 95% of the time, which means that if only one canal is found, then the practitioner better search diligently to find the second canal; not treating a canal in a case where it is present 95% of the time is purely unacceptable.

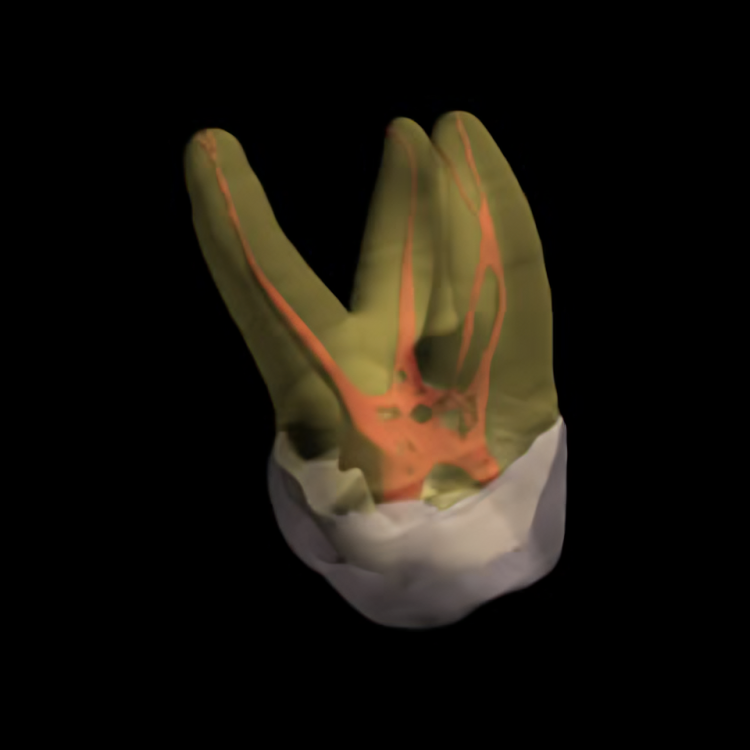

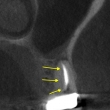

In other cases, the additional canal may only be present 75% of the time. The most common tooth that I find to have a root canal failure is the upper first molar, specifically the mesio-buccal root, which has two canals more than half the time. I generally find two canals in three out of four cases, yet nearly every time a patient presents with a failure in this tooth, it is because the original doctor missed the MB2 canal. Doing a root canal without a microscope greatly reduces the chances of treating the often difficult to find MB2 canal. Also, not having the right equipment makes finding this canal difficult. Not treating this canal often leads to persistent symptoms and latent (long-term) failure of the root canal. Using cone beam (CBCT) 3-dimensional radiographic imaging, like we have in our office, greatly assists in identifying the presence of this canal. In addition, when a patient presents for evaluation of a failing root canal, the CBCT is invaluable in helping us to definitively diagnose a missed canal.

The bottom line is that canals should not be missed because technology exists that allows us to identify and locate their presence. If a practitioner is performing endodontic (root canal) treatment, he or she needs to have the proper equipment to treat the full anatomy present in a tooth. Although getting a root canal from an endodontist may be slightly more expensive than getting one from a general dentist, there is a greater chance of savings in the long-term value of treating it right the first time.

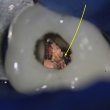

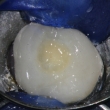

Click on thumbnails below for full size images, or read the entire case report HERE.Do root canals work

2. Incompletely Treated Canal

The second most common reason that I see for root canal failure is incompletely treated canals. This usually comes in the form of “being short”, meaning that if a canal is 23 millimeters long, the practitioner only treated 20 millimeters of it. Being short increases the chance of failure because it means that untreated or unfilled root canal space is present, ready for bacteria to colonize and cause infection.

Three reasons why a root canal treatment was shorter than it should be can be natural anatomy that does not allow it (sharp curves or calcifications), ledges (obstacles created by an inexperienced practitioner, a practitioner not using the proper equipment, or even an experienced practitioner in a complex situation), or pure laziness – not taking the time to get to the end of the canal.

Two factors that contribute to successfully treating a canal to length are proper equipment and experience. One example of proper equipment is an extra fine root canal file. Having the smallest most flexible root canal file (instrument used for cleaning) allows the practitioner to achieve the full length of the canal before damaging it in ways that are not repairable. If the doctor is using a file that is too large (and therefore too stiff) then he may create a ledge that is impossible to negotiate and will therefore result in not treating the full canal and could possibly lead to failure. Endodontists generally stock these smaller files, and general dentists often do not. Ledges can occur even with the most experienced doctor, but experience and the proper equipment will greatly reduce their occurrence.

The second factor that contributes to successfully treating a canal to length is experience. There is no substitute to having treated that particular situation many times before. Because endodontists do so many root canals, they develop a sensitive tactile ability to feel their way to the end of a canal. They also know how to skillfully open a canal in a way that will allow for the greatest success. Root canal treatment from an experienced endodontists greatly increases the chances that the full length of the canal will be treated and that failure will be reduced.

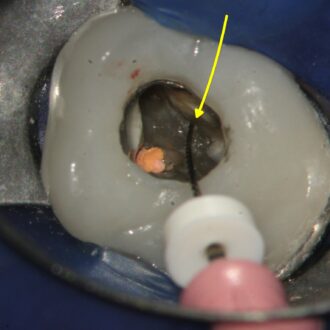

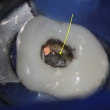

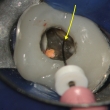

Click on thumbnails below for full size images.Lower Molar Re-treatment

3. Tissue

The third reason I see for root canal failure is tissue that remained in the tooth at the time of the first root canal. This tissue acts as a nutrient source to bacteria that can re-infect the root canal system. Root canals naturally have irregular shapes that our uniformly round instruments do not easily clean. Two common reasons why tissue is left in a root canal is lack of proper lighting and magnification, which is achievable with a dental operating microscope, and a root canal that was done too quickly.

Immediately before filling a root canal space that I have cleaned, I stop to inspect the canals more closely by drying them and zooming in with the microscope to inspect the walls under high magnification and lighting. Even when I think I have done a thorough job, I will often find tissue that has been left along the walls. This tissue can be easily removed with experienced manipulation of the root canal file under high magnification.

The second reason why tissue may remain in a root canal treated tooth is that it was done too quickly. I am completely aware that the patient (and the doctor) want the root canal to go as quickly as possible, but one of the functions of the irrigant used to clean during root canal treatment is to digest tissue – the longer it sits there, the cleaner the tooth gets. This is good because areas that are not physically touched with a root canal instrument can still be cleaned by the cleaning solution. If a root canal is done too rapidly, the irrigant does not have time to work and the tooth does not become as clean as it possibly could be. Practitioners continually make judgment on when enough cleaning has occurred. Whereas we would love to have the patient’s tooth soak for hours, doing so just is not practical. Therefore we determine when the maximum benefit has been achieved within a reasonable time period. If a root canal is done too rapidly and has not been thoroughly flushed then tissue may still remain and latent failure of the root canal may occur.

4. Fracture

Another common reason for root canal failure is root fracture. Although this may affect the root canal treated tooth, it may not be directly related to the root canal treatment. Cracks in the root allow bacteria to enter places they should not be. Fractures can occur in teeth that have never had a filling, indicating that many of them simply are not preventable.

Fractures may also occur due to root canal treatment that was overly aggressive at removing tooth structure. This is more common with root canals performed without magnification (such as the dental operating microscope) because the practitioner needs to remove more tooth structure to allow more light to be present.

Sometimes a fracture was present at the initial root canal treatment. When a fracture is identified, many factors go into determining if root canal treatment should be attempted. The prognosis in the presence of a fracture will always be decreased, but what we can never know is by how much. Sometimes the treatment lasts a long time, and sometimes it may only last six months. Our hope is that if root canal treatment was chosen to treat the tooth, then it will last a long time.

Fractures generally cannot be seen on an x-ray (radiograph). However, fractures cause a certain pattern of infection that can be seen on the radiograph which allows us to identify their presence. The cone beam (CBCT) 3-dimentional imaging system in our office can show us greater radiographic detail that helps us determine if a crack is present better than traditional dental radiographs. I have had many cases where I decided that root canal treatment or re-treatment would not solve the problem because the likelihood of a fracture was too high to justify treatment to save the tooth.

5. Leakage

The goals of root canal treatment is to remove tissue, kill bacteria, and seal the system to prevent re-entrance of bacteria. All dental materials allow leakage of bacteria; our goal is to limit the extent of leakage. At some unknown point the balance tips and infection can occur. The more measures we take to prevent leakage, the more likely success will occur. Four measures that can help reduce root canal failure due to leakage are rubber dam isolation, immediate permanent fillings, orifice barriers, and good communication with your general dentist.

Rubber Dam

A root canal should never be done without using the latex (or non-latex) barrier called a rubber dam. I was taught in school that root canal treatment without a rubber dam constitutes malpractice, and most practitioners would agree on that point. The rubber dam protects the patient in two ways. The first way that the rubber dam protects the patient is that it prevents small instruments from falling to the back of the mouth and being aspirated. The second way the rubber dam protects the patient is that it prevents bacteria rich saliva from entering the tooth and allowing for infection. A root canal done without a rubber dam is doomed to failure from bacteria. Although not required, use of the rubber dam at the time the access is restored can also hedge against failure from bacterial leakage. The first step to a successful root canal is to prevent the entrance of bacteria by using a rubber dam.

Permanent Filling (Build-Up)

When a root canal is finished by a specialist, it is a highly common practice for the endodontist to place a cotton pellet and a temporary material, which will then be replaced by the patient’s general (restorative) dentist. This temporary material can begin leaking right away, but is generally sufficient for a period of 7-21 days while the patient makes an appointment with their general dentist.

The best way to reduce the chance of bacterial leakage is to have a permanent filling placed at the time root canal treatment is finished. This will assure that the tooth is sealed as much as possible against bacterial leakage. This filling is called an access restoration or a build-up. Although many endodontists place restorations to seal the access, many still place a temporary. Whether the patient receives a permanent filling or a temporary filling is largely dependent on a combination of factors including the practice philosophy of the endodontist, the preferences of the referring dentist, the complexity of the treatment plan, and the time allotted for treatment.

Orifice Barriers

When a permanent filling cannot be placed at the time a root canal is completed, an orifice barrier is the next best alternative. The opening to the canals is called an orifice, and the barrier can be a variety of materials. The material used in our office is a purple flowable composite that is bonded to the floor of the tooth and hardened with a high intensity light. Research will never prove whether this technique is effective or not in improving the long-term prognosis, but the general feeling in the endodontic community is that a bonded orifice barrier is better than nothing.

Good Communication and Timely Follow-up with the Restorative Dentist

Finally, leakage can be reduced when the patient sees their restorative dentist as soon as possible after root canal treatment has been completed. This can be accomplished when there is efficient communication between the endodontist and the restorative dentist. In our office we also send a monthly summary of patients to each doctor that they can use as one more layer to confirm that treatment on their patient has been completed and that the patient needs to be seen as soon as possible for restorative treatment. Much of the responsibility for timely restorative care is in the hands of the patient. Patients who delay restorative treatment after root canal therapy are risking failure of their root canal treatment, which may necessitate re-treatment at their expense. Patients should not delay in getting their root canal treated tooth permanently restored with a filling and in many cases with a crown.

The best way a patient can prevent failure of a root canal is to seek care from a practitioner like an endodontist that has experience, that has the proper equipment (including a microscope and possibly a cone beam CBCT 3D imaging), and to receive timely restorative treatment either at the time root canal treatment is completed or shortly thereafter.

To our readers: This article is number one in the world for people searching the topic ‘Do root canals work?’